Ingredients: Konstance Patton creates across mediums

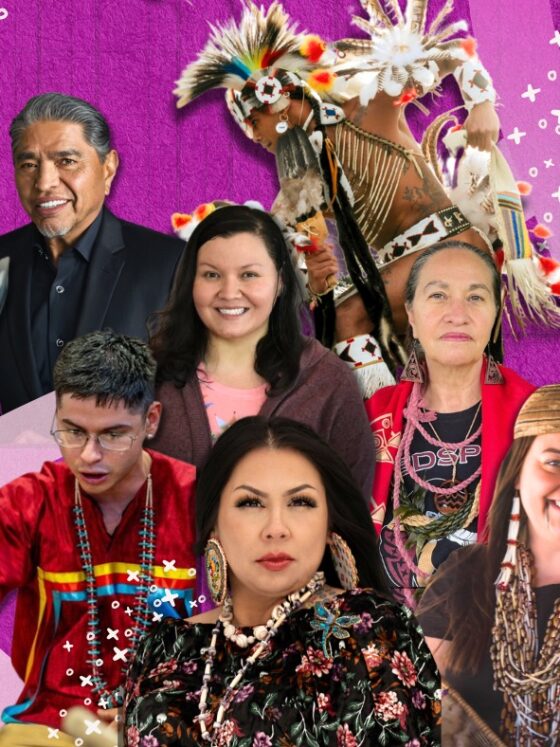

Fry Bread met up with Konstance Patton, a ‘Black Indian’ (Anishinaabe) woman from Detroit, at her studio in Brooklyn. Konstance is a multi-talented artist, working across mediums from painting to embroidery, sculpture to beadwork, murals to multi-media and more. Her work is currently on display at the Detroit Institute of Art’s Contemporary Anishinaabe Art: A Continuation.

Konstance shared with us, about her family and her work, as she prepared to move back to Michigan.

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Fry Bread: What brought you out here to New York?

Oh, man. Oh, I mean, it’s New York. When I was really young, I was opened up to the world by my grandmother. I lived with my grandmother, Mildred. And she was super curious about the world and got all the magazines, Reader’s Digest and Architectural Digest, to Scientific American. And I was able to kind of see the world. Very early, I was curious about other places. As I got older and it became time for me to decide on what type of journey that I was going to take, New York felt like a place where I can have a jumping off point. Many of the greats came here, many people have studied here, and I actually didn’t intend to stay here for long. It kind of gave me a pretty soft landing. It also beat me up all the time.

I come from a long line of chiefs and artists and actually, I have a festival called Potluck, Detroit. It’s a healing art festival at Talking Do Studio and collaboration with them and my sister, who’s a holistic health practitioner.

I grew up in a very Indigenous, or we just say Indian. I’m not going to say Indigenous no more. I’m saying Indian with a capital I-N-D-I-A-N, okay? Indian. We grew up in a very Indian household in Detroit, because my grandmother left the rez. She left Petoskey, the house that they lived in.

Fry Bread: As in, northern Michigan?

Way up there in the pinky. She was born up in Charlevoix, and she’s buried there with my grandfather and lots of my family. I actually spent a lot of time up there. Typically in the winters, I’ll go and spend time up there. But yeah, I grew up in the Indian way. If you walked in [our house], there’s everything you think – plates with the wolves and the drums and the feathers and all that. But also, we played Nintendo.

Fry Bread: As a Black person, we always hear and say things, “I have Indian in my family…”

Well, a lot of them do, though. That’s the thing. And as I’ve gotten older, I really believe that a lot of us do. And it’s just a fact of proving it, right? And the energy it takes to give a fuck to even do that, which I have friends that don’t. You know, my family has and we have all that information, which is really beautiful, but that’s really what motivates me to keep making my work too, and I make sure to pass on what was passed on to me.

I’m a Black girl, I’m an Indian girl. I’m not half of anything. I’m just a person that’s whole.

Konstance Patton

Fry Bread: Did you see they brought the powwow back to Detroit?

Yeah, they should. I mean, I’m in an exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts, and it’s been 30 years since they’ve had an exhibition with Anishanabe artists, and I’m the only black artist in it that is Anishanabe, and I’m the only artist from Detroit in it.

Fry Bread: How do you educate people about your Afro-Native experience?

You know, I was talking to my friend about it yesterday and we talked about some of the questions that I get, and that’s a big one, about my identity. I’m happy to talk about it. I’m a Black girl, I’m an Indian girl. I’m not half of anything. I’m just a person that’s whole. When people are, ‘oh, we’re part this and part that.’ It feels very reductive. I identify myself as both. I’m a Black Indian girl. I have the stories that were passed down to me, you know? That is what I really have been researching and trying to unpack.

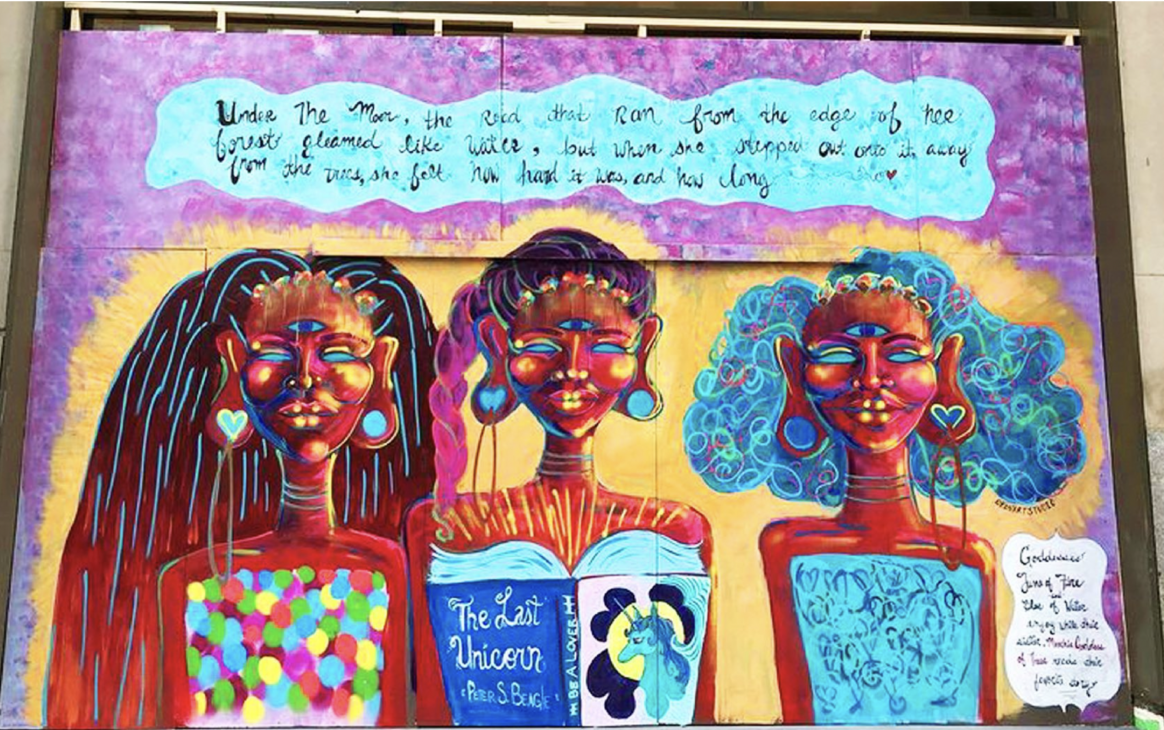

But as far as the work that I make, I draw Black girls or blue girls or pink–they’re really goddesses. They’re supposed to represent the divine feminine itself or aspects of it or aspects of people that I’ve met–the energy.

Fry Bread: There’s no one singular approach to your work.

I’m still contemporary. I wear Jordans. But it really rubs people the wrong way, too. When I was growing up, I’ve had experiences and my sisters, we’ve had experiences with racism – from everybody. It’s not my problem. That’s honestly how I feel about it. I used to get really upset about it or try to make really Indian work with a whole headdress. But I really want to capture the idea of a goddess right now or what would she look like here, right now, in Detroit. You know what I mean? What would this goddess look like? What would she look like if she have a little bling in her mouth? You know what I mean? She got a little Afro pump, puffs, and she’s vibing with her people and nature and I’m more concerned with depicting whatever comes out of me, then explicitly trying to insert my identity into it, because I think it already is.

Fry Bread: You’ve been here in New York for more than 20 years, but how do you maintain your Detroit connections?

A lot of the work that I have here, I’ve started in Detroit. Some of these pieces, I’m going to Detroit to finish them. I always had the plan, and the goal, and the want to go learn as many things as I could in the world and come back with this tool bag of stuff that I can start to share – and also learn because a lot of the people didn’t leave [Detroit]. I think it’s kind of a crazy place. And it’s a kind place. It’s beautiful and all these things. It’s rough too, but it’s a beautiful place.

I never really left there. I always made sure that I went and did a project there, especially in the earlier days, when I was younger and I was broke. And at this point, I’m out there, probably a third of my time.

Fry Bread: Would you move back to Detroit?

There’s been times where I’ve lived in other places and I’ve always maintained this [Brooklyn] apartment. But I’m embracing a new chapter right now, especially after I got injured [her foot was crushed by a car], everything changed. My whole life has changed in the last few months. And knowing that any time that there’s some catastrophe, there is something that grows out of it. And I’m really kind of looking forward, and have great energy towards whatever it is that’s coming next. I know that Detroit’s a big part of it. I’m very excited to move back.

Fry Bread: What materials are you working with lately? And how are you adapting around your injury?

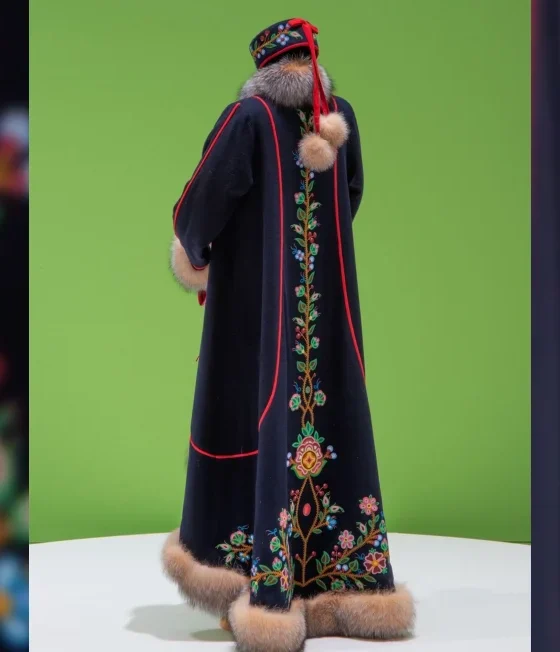

Right now, I’m doing a lot of embroidery. I’m doing a lot of bead work, and sculpting. I’ve been sculpting, because I can’t really do murals right now. I’m really hungry for materials and touching things. There’s not one thing I’m really working on all the time, specifically, usually, it’s excellent for my ADD because I can kind of have three different projects happening at the same time, in various stages.

Fry Bread: Do you consider yourself a veteran or elder? Or do you still feel like you have a lot to learn?

Oh, kind of. I feel like a baby elder, I think. Yeah. I feel like a young elder.

Fry Bread: How’s that feel?

I am thirsty for learning. That’s one of the things. I’m going back into materials I’m not familiar with,and things I’ve used 20 years ago. I haven’t touched oil paint since I was 19 years old. I actually had to ask one of my mentees to give me a little workshop on it. I’ve been thirsty for materials and messiness over the years that I feel very comfortable in many, many creative situations. There’s not a ton of things that I haven’t wanted to learn. I’ll say it that way. For example, I haven’t gone into stonework. But I might one day, you know?

Fry Bread: What does ‘being messy’ mean, exactly?

It’s touching things and changing them. It’s the alchemy of it. I have this puppet I started long ago, and we kind of never finished it. And then we started something else, and I’m thinking ‘oh,I can spray paint that real quick.’ I actually was thinking of it today – I’ll probably paint it and I’ll take it home with me. But at this point, I’ll know how to do it, and be comfortable with those materials.

Fry Bread: You say your family does a lot of art. Do you think that they’re proud of you?

I know they are. I know they are because they’ve told me. They’re stoic. They’ll tell you they’re proud of you without words, you know?