OPINION: The Memory Blade

Why Native Art Stayed Sharp While Settler Art Went Soft: While white Midwestern artists buried the past in nostalgia, Native artists preserved memory with an edge that still cuts

From Todd Epp, Northern Plains News

While white Midwestern art mellowed into nostalgic wallpaper, Native American art never dulled. It never lost its edge.

Why?

Because Native artists were never granted the privilege of forgetting.

For them, trauma wasn’t a historic episode—it was inherited memory. The removals, the boarding schools, the broken treaties, and the sterilization campaigns didn’t just happen. They linger. These aren’t relics. They are scars still healing, wounds still open. While white settlers mythologized their struggles, Native artists documented survival in real time.

Their art was never just decoration. It was resistance.

Memory as Resistance

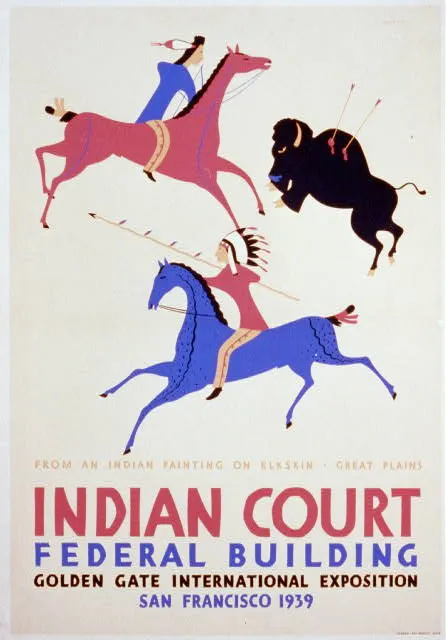

From winter counts inscribed on buffalo hides to ledger drawings on government-issued paper, Native creativity captured memory as a form of defiance. It said: “We’re still here. We remember. There is no room for sentimentality. There is no softening of the past when its sharp edges are ever-present.”

Consider Oscar Howe. His angular, explosive style challenged the very notion of what Native art was allowed to be. His Umine Wacipi (War and Peace Dance) doesn’t flatter—it confronts. It pulses with motion, tension, and unspoken grief. He refused to be boxed in by tradition or settler expectations.

He wasn’t alone.

Arthur Amiotte’s dense collages mix humor with historical weight. Dyani White Hawk fuses beadwork and abstraction into decolonized landscapes. Dwayne Wilcox adds satire to traditional ledger motifs. Artists like Laura Youngbird, Angela Babby, Linda Haukaas, JoAnne Bird, and Rhonda Holy Bear each bear witness in their own distinctive, unsoftened ways. They keep the blade sharp.

The Comfort of Nostalgia

Meanwhile, artists like Terry Redlin offered white America a nightlight. Their works were comfort food: snowy barns, amber sunsets, wildlife frozen in pastoral glow, art as reassurance, art that helped forget.

Where Native artists held a mirror to survival, settler artists hung curtains over the past.

Native artists, by contrast, offer a blade—memory that cuts through silence, myth, and the tyranny of nice.

The Art That Still Burns

Why the difference?

Because repression was not a coping mechanism—it was the enemy. Native art couldn’t collapse into comfort. It didn’t have that option. It had to tell the truth, even when the truth hurt.

Midwestern settler art found refuge in forgetting. It painted over hardship with soft brushstrokes and stoic smiles, burying the past under snowdrifts and politeness.

But Native art didn’t forget.

And that’s why it still burns.

That’s why it still speaks.

That’s why it still matters.